Сердечно-сосудистые заболевания (ССЗ) остаются ведущей причиной смертности в мире [1, 2]. Согласно отчету Всемирной организации здравоохранения (ВОЗ), в 2015 г. было зарегистрировано 17,7 млн смертей, связанных с кардиоваскулярными болезнями, что составляет 31% от общей смертности в мире [3]. В развитых странах эти значения еще выше: ежегодно только в Европе на долю ССЗ приходится 42% смертей у мужчин и 51% у женщин [1].

Помимо традиционных факторов риска ССЗ, таких как возраст, ожирение, артериальная гипертензия (АГ), сахарный диабет (СД), курение, нарушения липидного обмена, злоупотребление алкоголем, гиподинамия в генезе ССЗ, одной из ключевых причин развития и прогрессии атеросклероза и, как результат, ишемической болезни сердца (ИБС), инфарктов и инсультов может быть хроническое воспаление, в том числе свойственное некоторым ревматическим заболеваниям [4, 5]. Не является исключением и подагра, представляющая собой наиболее частую форму артрита в мире, при которой риск ССЗ выше популяционного [6, 7], а одной из возможных причин этого считается именно хроническое кристалл-индуцированное воспаление [8]. Отметим в связи с этим, что в последние десятилетия сохраняется тенденция роста заболеваемости и распространенности подагры [9].

ГИПЕРУРИКЕМИЯ КАК ФАКТОР РИСКА СЕРДЕЧНО-СОСУДИСТЫХ ЗАБОЛЕВАНИЙ

Непременным атрибутом нелеченой подагры и единственной доказанной причиной ее развития является гиперурикемия (ГУ): ее наличие отождествляется с высоко вероятным развитием подагры, эндотелиальной дисфункцией и оксидативным стрессом, а также ассоциацией с ССЗ. При этом важно, насколько реальна перспектива снижения риска развития ССЗ при применении уратснижающих препаратов.

Весомое подтверждение гипотезы о том, что ГУ следует рассматривать как одну из причин развития и преждевременной смерти от ССЗ, было получено еще на рубеже веков в рамках крупнейшего проспективного эпидемиологического исследования NHANES I (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey), показавшего четкую взаимосвязь между увеличением смертности, ассоциированной с ССЗ, и уровнем мочевой кислоты (МК) сыворотки [10].

На сегодняшний день исследований, целью которых было установить, действительно ли ГУ оказывает негативное влияние сердечно-сосудистую систему и насколько это прогностически значимо, столь много, что это позволяет обобщать полученные данные в виде крупных метаанализов. В наиболее полном из них (958 410 участников из 29 проспективных когортных исследований) скорректированный относительный риск (ОР) развития ишемической болезни сердца (ИБС) для ГУ составил 1,13 (95% доверительный интервал (ДИ): 1,05–1,21), при этом для каждого увеличения уровня МК на 1 мг/дл многомерный ОР смертности от ИБС равнялся 1,13 (95% ДИ: 1,06–1,20) [11].

Аналогичные данные были получены и по результатам более раннего метаанализа Kim S.Y. et al. (26 исследований, 402 997 участников), выявившего независимое увеличение ОР у лиц с ГУ на 9% (ОР 1,09; 95% ДИ: 1,03–1,16), а смертности от ИБС – на 13% (ОР 1,13; 95% ДИ: 1,01–1,30) [12]. Каждое увеличение уровня МК сыворотки на 1 мг/дл давало прирост смертности от ИБС на 12%. Однако интересно, что если у женщин наличие ГУ соответствовало крайне высокому ОР смертности от ИБС (ОР 1,67; 95% ДИ: 1,30–2,04), то для мужчин он был не столь велик (ОР 1,09; 95% ДИ: 0,98–1,19).

Наконец, один из последних метаанализов (11 исследований, 11 108 участников, средняя продолжительность наблюдения 4,6–6,1 лет) показал независимую связь между ГУ и развитием кальцификации коронарных артерий: скорректированное отношение шансов (ОШ) наличия кальцификации составило 1,48 (95% ДИ: 1,23–1,79), при каждом повышении уровня МК сыворотки на 1 мг/дл риск ее прогрессирования увеличивался на 31% (ОШ 1,31; 95% ДИ: 1,15–1,49) [13].

В проспективном 5-летнем исследовании среди 4327 лиц старше 60 лет, страдающих АГ и рандомизированных в группу плацебо или диуретика хлорталидона, было изучено влияние ГУ на исходы ССЗ, включившие инсульт, ИБС и смертность от всех причин [14]. В группе активного лечения по сравнению с плацебо и после корректировки на соответствующие факторы увеличение риска инсульта или любого другого сердечно-сосудистого события не наблюдалось, тогда как скорректированное отношение рисков сердечно-сосудистых событий для наивысшего квартиля сывороточной МК, по сравнению с наиболее низким, составило 1,32 (95% ДИ: 1,03–1,69).

В большинстве работ за уровень МК сыворотки, соответствующий ГУ, были приняты «канонические» показатели: >360 мкмоль/л у женщин и >420 мкмоль/л у мужчин; они приблизительно соотносятся с уровнем МК, при котором начинает резко возрастать риск трансформации ГУ в подагру [15]. Правда, не ясно, соответствуют ли этой дефиниции реальные значения МК, оказывающие отрицательное влияние на риски ССЗ и смертность. Предположив, что пороговый уровень МК, обладающий потенциальными негативными эффектами на ССЗ, может находиться ниже указанных значений, было инициировано исследование URRAH (Uric Acid Right for Heart Health), идея которого была в пересмотре подходов к определению ГУ [16]. Ретроспективно была оценена связь между сывороточной концентрации МК, смертностью от всех причин, фатальным и нефатальным инфарктом миокарда, инсультом, коронарной реваскуляризаций и сердечной недостаточностью в когорте из 23 475 человек, преимущественно с наличием АГ (средний возраст 57±15 лет, 51% мужчин, длительность наблюдения более 20 лет). Исследование подтвердило независимую связь между уровнем МК, общей и сердечно-сосудистой смертностью; при этом для общей смертности наиболее значимый показатель снижения уровня МК составил всего 4,7 мг/дл (около 280 мкмоль/л), а значения выше указанного ассоциировались с более чем полуторакратным ОР (1,51; 95% ДИ: 1,40–1,63; р <0,001). Расчетное пороговое значение МК для оценки смертности от ССЗ составило 5,6 мг/ дл (чуть больше 330 мкмоль/л), при отношении рисков для превышения этого значения 1,59 (95% ДИ: 1,43–1,76; р <0,001). ГУ ассоциировалась и с фатальным инфарктом миокарда (ОШ в общей популяции 1,146; 95% ДИ: 1,060–1,239; р=0,0007) при пороговом уровне МК 5,70 мг/дл (примерно 340 мкмоль/л), однако у мужчин, в отличие от женщин, связь между этими параметрами не была достоверной.

Таким образом, можно предположить, что в генезе ССЗ, помимо формирования кристаллов уратов, могут иметь место и другие механизмы, поскольку пороговый уровень МК, который отождествляется с неблагоприятным исходом ССЗ, ниже классических значений. Причины гендерных отличий, которые были обнаружены и в ряде других, помимо вышеуказанных, исследований [17, 18], могут быть обусловлены различием у мужчин и женщин генетически контролируемого метаболизма МК [19], а также влиянием половых гормонов: ГУ у женщин выступает мощным фактором развития гипертрофии левого желудочка именно в постменопаузальном, но не предменопаузальном периоде [20].

ВЛИЯНИЕ ГИПЕРУРИКЕМИИ НА АРТЕРИАЛЬНУЮ ГИПЕРТЕНЗИЮ

Среди возможных путей влияния ГУ на риск ССЗ в первую очередь следует выделить развитие АГ. ГУ приводит к повышению АД, что особенно ярко проявляется в юном возрасте. При этом АГ характеризуется частой рефрактерностью к гипотензтивной терапии [21–23]. Уже в первых классических экспериментах на животных было установлено, что искусственное создание ГУ сопровождается повышением АД, связанной с нарушением почечной гемодинамики и гломерулярной гипертрофией, а лекарственная коррекция ГУ приводит к нормализации АД и редукции поражения почек [24, 25].

Особого внимания заслуживает более поздняя работа Sanchez-Lozada L.G. et al., в которой индукция ГУ у крыс была спровоцирована естественным путем благодаря включению в рацион подопытных животных больших количеств фруктозы [26]. Одна из групп подопытных животных получала обогащенный фруктозой рацион в первые 4 нед, а после совместно с фебуксостатом на протяжении еще такого же периода. Исходно прием крысами фруктозы ассоциировался как с ГУ, так и повышением АД, сывороточных уровней инсулина и триглицеридов. Через 4 нед приема фебуксостата, несмотря на продолжающееся потребление фруктозы, указанные обменные нарушения и значения АД приходили в норму параллельно снижению уровня МК сыворотки. По сравнению с животными, продолжавшими питаться фруктозой и получавшими плацебо без фебуксостата, у основной подопытной группы отмечалось снижение давления в почечных клубочках, восстановление исходно суженных при фруктозной диете почечных сосудов и афферентных артериол.

Результаты наиболее крупного метаанализа, включившего 25 исследований и суммарно 95 824 пациента, позволили заключить, что увеличение концентрации МК сыворотки на 1 мг/ дл соответствовало возрастанию риска АГ в среднем на 15% (ОР 1,15; 95% ДИ: 1,06–1,26) [27]. В целом же наличие ГУ было связано с почти в 1,5 раза большей вероятностью развития АГ (ОР 1,48; 95%ДИ 1,33–1,65).

Аналогично ГУ предшествовала развитию АГ почти у 90% подростков в исследовании Feig D.I. et al., а снижение уровня МК при назначении ингибиторов ксантиноксидазы, напротив, приводило к коррекции показателей АД [28].

Представляется, что влияние ГУ на показатели АД может быть обратимым, если оно реализуется до формирования стойкой АГ. Например, среднее снижение систолического АД при применении уратснижающих препаратов детьми в возрасте 11–17 лет с предгипертензией составило 10,2 мм рт.ст., а диастолического АД – 9,0 мм рт. ст. При этом на фоне приема плацебо данные показатели повысились на 1,7 и 1,6 мм рт. ст. соответственно [29]. Медикаментозное снижение МК сыворотки также приводило к значительному снижению показателей системного сосудистого сопротивления. Однако у взрослых влияние уратснижающей терапии как на показатели АД, так и на активность ренин-ангиотензиновой системы не столь явное [30, 31].

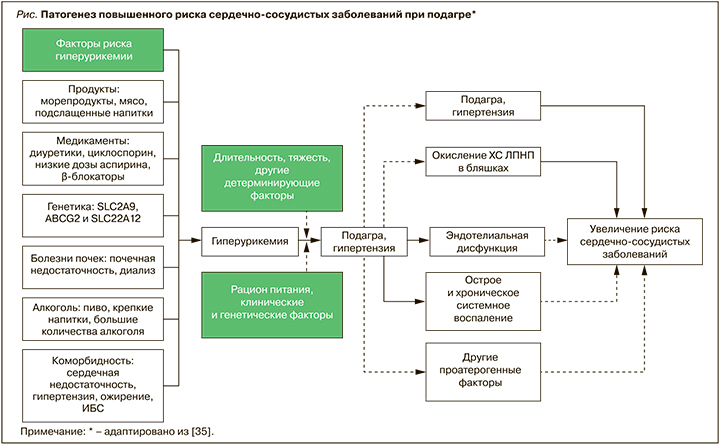

Возможно, в патогенезе ССЗ ключевое значение имеет не только ГУ как таковая, но и сопутствующая высокая активность ксантиноксидазы, которая генерирует продукцию активных форм кислорода и, подавляя синтез оксида азота, способствует повреждению эндотелия [32]. Наличие некоторых аллелей гена ксантинооксидредуктазы приводит к синтезу МК и ассоциируется с развитием АГ с увеличенным пульсовым давлением; в то же время ингибирование ксантиноксидазы, помимо снижения сывороточного уровня МК, уменьшает оксидативное поражение сосудов и рассматривается как потенциально важная точка приложения для лечения и профилактики ССЗ, хронической болезни почек и других заболеваний и состояний [33, 34]. Среди других факторов, обусловливающих негативное влияние подагры на риск ССЗ, можно отметить повышение содержания окисленных липопротеинов низкой плотности (ЛПНП), дислипидемию и острое и/или хроническое воспаление (рис.) [35].

Хроническое микрокристаллическое воспаление сопровождается гиперпродукцией провоспалительных цитокинов, прежде всего интерлейкина-1 (ИЛ), играющего ключевую роль в генезе атеросклероза [36]. Именно воспаление способствует развитию окислительного стресса и вкупе с активацией ксантиноксидазы образованию свободных радикалов, которые, в свою очередь, приводят к окислению ЛПНП и развитию атеросклероза [37, 38]. При этом применение блокаторов ИЛ-1 вызывает как снижение риска общей и сердечно-сосудистой смерти, так и редукцию приступов подагрического артрита [39], в том числе у лиц с бессимптомной ГУ и вне зависимости от сывороточного уровня МК [40].

В последние годы сердечно-сосудистые риски у пациентов с подагрой и бессимптомной ГУ нередко рассматриваются отдельно. Например, согласно данным анализа смертности у пациентов с подагрой и бессимптомной ГУ Тайваньского национального регистра, скорректированное отношение риска смерти от любой причины у больных подагрой в сравнении с остальной популяцией (лица с нормоурикемией) составило 1,46 (95% ДИ: 1,12–1,91), а при бессимптомной ГУ – только 1,07 (95% ДИ: 0,94–1,22) [41]. В отношении смертности от ССЗ при подагре этот показатель был равен 1,97 (95% ДИ :1,08–3,59), а при бессимптомной ГУ – лишь 1,08 (95% ДИ: 0,78–1,51).

В 2006 г. было проведено первое крупное проспективное рандомизированное контролируемое исследование с участием 12 866 мужчин, которое продемонстрировало, что подагра, независимо от ГУ, является фактором риска острого инфаркта миокарда (ОШ 1,26; 95% ДИ: 1,14–1,40) [8]. По аналогии с ГУ при подагре у женщин этот риск выше, чем у мужчин. В крупнейшем популяционном исследовании был установлен высокий риск острого инфаркта миокарда у женщин с подагрой (ОШ 1,39; 95% ДИ: 1,20–1,61), но не у мужчин (ОШ 1,11: 95% ДИ: 0,99–1,23) [42].

Отдельного внимания заслуживает исследование Singh J.A. et al., в котором авторы, не подвергая сомнению негативное влияние ГУ и подагры на вероятность развития ССЗ, попытались ответить на вопрос, следует ли рассматривать подагру как эквивалент такому фактору риска, как сахарный диабет (СД) [43]. Были рассмотрены 4 когорты пациентов: с СД (n=232 592), подагрой (n=71 755), обоими заболеваниями (n=23 261) и их отсутствием (n=1 010 893); средняя длительность наблюдения составила 427 дней. Сначала сравнивалась вероятность инфаркта миокарда и (отдельно) инсульта у пациентов с СД, подагрой или их сочетанием по сравнению с лицами, не имеющими этих заболеваний. Максимальные риски отмечались при сочетании СД и подагры. Далее в качестве референтного значения был взят СД: выяснилось, что при комбинации СД и подагры вероятность как инфаркта, так и инсульта была примерно в 1,4 раза выше, чем при наличии только диабета. Отношение рисков инфаркта миокарда у больных подагрой было достоверно меньше, чем при СД, тогда как в плане влияния на развитие инсульта подагра была столь же мощным фактором развития инсульта, как и диабет.

В связи с вышесказанным следует упомянуть об очень частом сочетании подагры не только с СД и АГ, но и нарушениями липидного обмена и ожирением, в том числе в рамках метаболического синдрома. Это также может быть одной из важнейших причин высокой частоты общей и сердечно-сосудистой смерти у пациентов с подагрой [44]. Тем не менее, по данным цитированных исследований, где, помимо традиционных кардиоваскулярных факторов риска, рассматривалось влияние на развитие ССЗ проявлений подагры, именно тяжелое течение этого заболевания (максимально высокий сывороточный уровень МК и наличие подкожных тофусов), а также повышенный уровень С-реактивного белка были независимыми предикторами общей и сердечно-сосудистой смертности пациентов с подагрой [8, 45].

ВЛИЯНИЕ УРАТСНИЖАЮЩЕЙ ТЕРАПИИ НА СЕРДЕЧНО-СОСУДИСТЫЙ ПРОГНОЗ

Для бессимптомной ГУ четких рекомендаций по медикаментозной коррекции до настоящего времени не существует [46]. Наличие клинически выраженной подагры в сочетании с ССЗ в соответствии с международными (EULAR) [47] и национальными (Ассоциация ревматологов России) рекомендациями [48] предполагает обязательное назначение уратснижающих препаратов (прежде всего ингибиторов ксантиноксидазы), независимо от уровня МК (если он выше целевого) и частоты приступов артрита. Еще более строго к проведению лекарственной терапии подагры требуют относиться авторы рекомендаций по лечению подагры, принятых в 2020 г. во Франции: исходя именно из высокого сердечно-сосудистого риска, они указывают на необходимость назначения уратснижающих препаратов всем без исключения пациентам с подагрой [49].

Эти работы создали необходимую базу для проведения соответствующих исследований по оценке влияния различных уратснижающих препаратов на риски ССЗ у пациентов с подагрой. В наблюдении Perez-Ruiz F. et al., длившемся около 4 лет, был проанализирован результат лечения подагры в когорте из 1192 больных с точки зрения риска фатального исхода в случае достижения или не достижения целевого уровня МК сыворотки (<360 мкмоль/л) [50]. За время наблюдения скончались 158 пациентов (13%); сывороточный уровень МК <360 мкмоль/л поддерживали чуть более 16% больных, при этом отношение рисков как общей, так и сердечно-сосудистой смерти при уровне МК ниже указанного было более чем в 2 раза меньшим: ОР 2,33 (95% ДИ: 1,60–3,41) и 2,05 (95% ДИ: 1,21–3,45) соответственно. Несмотря на столь впечатляющий результат, не ясно, достаточен ли указанный уровень МК для улучшения прогноза и не приведет ли к лучшему результату достижение еще более низкого целевого уровня МК. Проспективное когортное исследование, проведенное в Таиланде, выявило в 2,4 раза большее отношение рисков сердечно-сосудистой смерти (2,43; 95% ДИ: 1,33–4,45) у пациентов с подагрой, не получавших уратснижающие препараты, по сравнению с теми, кто не страдал подагрой и также не получал препаратов, влияющих на уровень МК [51]. Отношение рисков смерти от любой причины для тех же условий также оказалось большим у пациентов с подагрой, не использовавших уратснижающие препараты: 1,45; 95% ДИ: 1,05–2,00. У пациентов с подагрой, кто принимал уратснижающие средства, отношение рисков смерти от ССЗ и всех других причин было ниже, чем у больных подагрой, не получавших подобной лекарственной терапии (0,29; 95% ДИ: 0,11–0,80 и 0,47; 95% ДИ: 0,29–0,79 соответственно).

Спорными (вероятно, из-за разного профиля сердечно-сосудистой безопасности) остаются критерии выбора конкретного уратснижающего препарата. В 2018 г. были опубликованы данные рандомизированного исследования CARES (Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities), свидетельствующие о большей (на 4,3%) смертности от ССЗ среди пациентов, принимавших фебуксостат, по сравнению с аллопуринолом (3,2%; p=0,03) [52]. Практическим результатом этой работы стали рекомендации по ограничению использования фебуксостата, отнесение его ко второй линии уратснижающей терапии подагры и утверждение в качестве единственного препарата первой линии аллопуринола [53, 54]. Вместе с тем, принимая во внимание ряд серьезных методологических изъянов этой работы (большой процент пациентов, прекративших прием препаратов, несоответствие доз исследуемых средств, различия между группами по таким параметрам, как сопутствующая терапия, достигнутый целевой уровень МК, информация о частоте и длительности артритов, потребности в НПВП и др.), эти решения нельзя считать безапелляционными [55].

Так, Zhang M. et al. изучили вероятность развития инфаркта миокарда и инсульта у пожилых пациентов старше 65 лет (средний возраст 76 лет), сопоставив частоту этих сердечно-сосудистых событий у 24 900 больных подагрой, принимающих фебуксостат, и 74 700, получающих аллопуринол. Статистически значимых различий между группами найдено не было [56].

Более весомым и не менее значимым, чем CARES, следует признать недавнее исследование FAST (The Febuxostat versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial): в нем на протяжении в среднем 4 лет наблюдались пациенты с подагрой, рандомизированные в группы приема аллопуринола (n=3065) и фебуксостата (n=3063) [57]. В отличие от исследования CARES не все, а лишь 2046 (33,4%) участников FAST имели ССЗ в анамнезе. Первичной конечной точкой исследования служила госпитализация по поводу не смертельного инфаркта миокарда или наличие положительного биомаркера острого коронарного синдрома. Как показали результаты, частота не смертельного инфаркта или смерти из-за кардиоваскулярных осложнений не различалась в зависимости от того, получали ли они уратснижающий препарат в реальности, или от того, в какую группу они были рандомизированы. Это позволило минимизировать возможные статистические погрешности, связанные с частым отказом пациентов от приема исследуемых препаратов.

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Подагра в связи с наличием гиперурикемии, хронического микрокристаллического воспаления, повышенной активности ксантиноксидазы и окислительного стресса, а также проатерогенных коморбидных заболеваний вносит существенный вклад в развитие кардиоваскулярных заболеваний, определяя высокую общую и сердечно-сосудистую смертность среди больных. Последние данные показывают, что благодаря наличию кардиопротективных свойств у аллопуринола (а возможно, и у другого ингибитора ксантиноксидазы – фебуксостата) прием уратснижающих средств может считаться не только методом контроля клинического течения подагры и уровня мочевой кислоты, но и самостоятельным направлением снижения риска кардиоваскулярных осложнений у пациентов с этим заболеванием.