ВВЕДЕНИЕ В ПРОБЛЕМУ

Связь между гипертиреозом и фибрилляцией предсердий (ФП) хорошо установлена клиническими и экспериментальными данными. Предполагаемая распространенность ФП составляет 0,4–1% среди населения в целом и увеличивается с возрастом до 8% у людей старше 80 лет. ФП имеет сложную патофизиологию, сильно зависящую от коморбидных сердечно-сосудистых заболеваний (ССЗ), в частности сердечной недостаточности (СН). В результате ФП и СН часто сосуществуют, причем у почти 50% пациентов с тяжелой СН развивается ФП [1]. Также ФП нередко приводит к инсульту и сердечно-сосудистой смертности. Выявление модифицируемых факторов риска и потенциально обратимых причин имеет решающее значение для профилактики и лечения ФП [2].

Пандемия COVID-19 остается серьезной проблемой, поскольку поражает многие органы и системы органов, включая щитовидную железу (ЩЖ). Частота новых случаев ФП у пациентов с новой коронавирусной инфекцией в разных популяциях находится в пределах 4–8%, при этом такие случаи характеризуются более высоким числом осложнений и 60-дневной смертности [3, 4]. Госпитализация в отделение интенсивной терапии по причине ФП (относительный риск (ОР) 4,68; 95% доверительный интервал (ДИ): 1,66–13,18), вероятно, является следствием системных заболеваний, а не только прямого воздействия SARS-CoV-2 [5]. В этом контексте важен анализ множественных взаимосвязей гипертиреоза и ФП, лежащих в основе различных клинических ситуаций, ургентность которых увеличивается в условиях пандемии COVID-19.

В публикациях на стыке различных медицинских специальностей имеются разночтения в определении гипертиреоза: нередко в качестве его синонима используется «тиреотоксикоз», что определяет необходимость уточнения смыслового значения этих терминов.

Гипертиреоз характеризуется гиперметаболизмом и повышенными уровнями свободных тиреоидных гормонов в крови. Причиной гипертиреоза может быть усиление синтеза и секреции гормонов тироксина (T4) и трийодтиронина (T3), вызванное присутствием в крови стимуляторов ЩЖ или возникающее в результате ее аутоиммунной гиперфункции. Повышенный уровень тиреоидных гормонов может возникать и без усиления их синтеза вследствие деструктивных процессов в ЩЖ при тиреоидитах разного типа.

В свою очередь, термином «тиреотоксикоз» обозначают клинически выраженное заболевание. Тиреотоксикоз может быть следствием гипертиреоза при болезни Грейвса (аутоиммунный гипертиреоз), воспалении ЩЖ (тиреоидит), доброкачественной опухоли ЩЖ или воздействия факторов, влияющих на функцию оси «гипоталамус–гипофиз–ЩЖ» [6].

Гипертиреоз также может быть вызван синдромом приобретенного иммунодефицита (СПИД) наряду с антиретровирусной терапией [7]. Нередко в клинической практике встречается ятрогенный гипертиреоз, обусловленный побочными эффектами некоторых лекарственных средств (йодсодержащих препаратов, интерферона-альфа, интерлейкина 2 и др.) и передозировкой препаратов экзогенных тиреоидных гормонов. Риск развития ятрогенного гипертиреоза также увеличивается из-за нарушений абсорбции Т4 при патологии желудочно-кишечного тракта [8].

Гипертиреоз был признан фактором риска ФП более 30 лет назад [9]. Соответственно в различных кардиологических гайдлайнах при первоначальной оценке пациентов с ФП рекомендуется оценка функции ЩЖ [10]. Отметим, что гипотиреоз не считается фактором риска аритмий [11], однако может способствовать прогрессированию СН, которая, в свою очередь, связана с повышенной вероятностью развития ФП [1].

Помимо явного отклонения функционального состояния ЩЖ, субклинический гипертиреоз (СГ) выступает частым вариантом тиреоидной гиперфункции легкой степени. Неопределенность клинического значения субклинических дистиреозов с той поры, как Cooper D.S. и Biondi B. (2012) заострили внимание на этой проблеме [12], сохраняется, что привело к спорам о целесообразности их диагностического тестирования и возможного лечения. Критерием субклинической дисфункции ЩЖ служат аномальные уровни тиреотропного гормона (ТТГ) при концентрациях свободных тиреоидных гормонов в пределах референсного диапазона. Согласно результатам исследования NHANES III, СГ страдает 2–3% взрослого населения США [13]. По другим данным, распространенность СГ составляет 0,7–9% [14].

Кроме того, Роттердамское проспективное исследование с участием людей среднего и пожилого возраста показало, что риск ФП, внезапной сердечной смерти и снижения продолжительности жизни ассоциирован с уровнем св. Т4 еще в верхнем пределе референсных значений [15, 16], особенно у более молодых пациентов; при этом показатели ТТГ с развитием ФП связаны не были [17]. Позднее Baumgartner C. et al. (2017), проанализировав результаты систематического обзора проспективных когортных исследований из баз данных MEDLINE и EMBASE (n=30 085), пришли к схожим выводам: у эутиреоидных лиц более высокие уровни циркулирующего св. T4 (верхний квартиль референсного диапазона), но не уровни ТТГ, ассоциированы с повышенным риском развития ФП [2]. Следовательно, при анализе связей нарушений ритма сердца с гипертиреозами возникает необходимость рассмотрения не только классических вариантов гипертиреоза, когда имеются отклонения как ТТГ, так и свободных фракций тиреоидных гормонов, но и субклинических его форм.

МЕХАНИЗМЫ ВЛИЯНИЯ ТИРЕОИДНЫХ ГОРМОНОВ НА СЕРДЕЧНО-СОСУДИСТУЮ СИСТЕМУ

Тиреоидные гормоны играют большую роль в оптимальном функционировании сердечно-сосудистой системы. Они оказывают прямое действие на сердце за счет комбинации геномных и негеномных эффектов, участвуя в регуляции метаболизма, электрических свойств и функций сердца [11]. Соответственно хронические и острые изменения циркулирующих тиреоидных гормонов значимо влияют на электрофизиологию сердца, состояние кальциевых каналов и структурное ремоделирование. Явный гипертиреоз или более частый СГ нарушают эту регуляцию, способствуя развитию сердечных аритмий, в основном ФП [18].

Отметим, что из-за отсутствия в кардиомиоцитах дейодиназной активности миокардиальный эффект тиреоидных гормонов обусловлен периферическим превращением Т4 в активную форму гормона – Т3. Именно он обладает преимущественно геномными эффектами, регулируя экспрессию генов-мишеней через связывание с ядерными рецепторами в кардиомиоцитах. В результате Т3 стимулирует рецепторы тиреоидных гормонов различного типа. Так, в сердце присутствуют рецепторы β-типа, что объясняет положительный инотропный эффект тиреоидных гормонов на уровне миокарда. Высказано предположение, что Т3 регулирует гены, контролирующие клетки водителя ритма сердца (пейсмекеры), проявляя в этих клетках положительный хронотропный эффект; помимо этого, Т3 вызывает увеличение экспрессии β1-адренорецепторов в кардиомиоцитах, повышая чувствительность миокарда к действию катехоламинов. На периферическом уровне тиреоидные гормоны стимулируют тиреоидные рецепторы α1-типа эндотелиальных и гладкомышечных клеток сосудов, способствуя снижению периферического сопротивления и диастолического давления [19, 20].

Т4 имеет несколько документально подтвержденных негеномных эффектов; в значительной степени он считается прогормоном [19]. Среди негеномных эффектов ТГ в отношении кардиомиоцитов – влияние на мембранные ионные каналы Na+, K+ и Ca2+, функцию митохондрий сердца, а также регулирование биоэнергетического статуса [20]. Именно дисфункция Ca2+-каналов, наряду с изменением экспрессии и функции других ионных каналов и нарушением межклеточного взаимодействия, опосредованного каналом коннексина, по всей видимости, выступает решающим механизмом в проаритмической передаче сигналов тиреоидных гормонов [1]. Наряду с этим T3 уменьшает вариабельность сердечного ритма за счет снижения тонуса блуждающего нерва, повышая риск аритмий; роль тиреоидных гормонов в аритмогенезе связана и с увеличением триггерной активности или автоматизма в кардиомиоцитах легочных вен [21]. Кроме того, при гипертиреоидном состоянии увеличивается экспрессия рецепторов ангиотензина II в миокарде [22].

Tribulova N. et al. в своей работе (2020) констатируют, что такая клинически значимая и потенциально опасная для жизни аритмия, как ФП, возникает из-за нарушений электрической активности вследствие целого ряда различных факторов, связанных с инициацией и распространением импульса [18]. Первое происходит из-за повышенного автоматизма кардиомиоцитов или триггерной активности – ранней постдеполяризации (РПД) или отсроченной постдеполяризации (ОПД). Последняя, в свою очередь, обусловлена блокадой проведения, способствующей возвратному возбуждению (re-entrant excitation), нарушениями в межклеточных коннексиновых каналах, структурным ремоделированием миокарда (гипертрофией и/или фиброзом, ожирением) и вариациями рефрактерных периодов. Гормоны ЩЖ могут быть вовлечены во все эти механизмы, а также в модуляцию автономной нервной системы и ренин-ангиотензин-альдостероновой системы (РААС), которые влияют на аритмогенез (рис. 1) [18]. Авторы подчеркивают, что при некоторых различиях нарушения электрической активности при ФП и фибрилляции желудочков схожи.

Другая возможная связь между функциональным состоянием ЩЖ и сердечно-сосудистой системой определяется нарушениями циркадного ритма. Эндогенные (генетические дефекты) и экзогенные (хроническая посменная работа, срыв биоритмов и нарушение сна) факторы нарушают систему суточного ритма, в которой важную роль играет ось «гипоталамус–гипофиз–ЩЖ». Существует точка зрения, что неправильные циркадные часы увеличивают риск заболеваний ЩЖ [23]. Так, Allada R. и Bass J. (2021) считают, что доказанная связь хронического нарушения циркадного ритма с повышенным риском ожирения, сахарного диабета и ССЗ дополнительно подтверждает ассоциацию между дисфункцией ЩЖ и риском ССЗ [24]. И, наоборот, заболевания ЩЖ нарушают циркадную систему тканеспецифичным образом [25].

Помимо циркадных ритмов, функция ЩЖ тесно связана с сезонными ритмами. Дискуссия о сезонности уровней ТТГ продолжается; основные механизмы сезонной регуляции заболеваний ЩЖ еще предстоит выяснить [23].

ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗ И ФИБРИЛЛЯЦИЯ ПРЕДСЕРДИЙ: ФАКТОРЫ РИСКА И ПОСЛЕДСТВИЯ

ФП признана наиболее частой наджелудочковой аритмией у пациентов с тиреотоксикозом [26]. От 10 до 25% пациентов с гипертиреозом страдают ФП, причем верхний предел этого диапазона приходится на мужчин ≥60 лет. И, напротив, только 5% пациентов с гипертиреозом <60 лет страдают ФП. Тип ФП при этом чаще стойкий, а не пароксизмальный [27].

Факторы риска ФП у пациентов с гипертиреозом аналогичны таковым в общей популяции: помимо возраста, это ишемическая болезнь сердца, застойная СН, мужской пол, пороки клапанов сердца. Более того, при гипертиреозе с наличием ФП были связаны и другие факторы, включая ожирение, хроническое заболевание почек, протеинурию, женский пол, концентрации св. Т4 и трансаминаз [22]. Более высокий риск ФП отмечен при токсическом многоузловом зобе по сравнению с болезнью Грейвса [28]. Учитывая высокую частоту ФП у пациентов старше 60 лет с тиреотоксикозом, ранний скрининг на ТТГ и свободные фракции Т4, Т3 особенно важен для выявления дисфункции ЩЖ у этой демографической группы пациентов.

Развитие ФП может быть связано с несколькими механизмами: повышенным давлением в левом предсердии, приводящим к увеличению массы левого желудочка и нарушению релаксации желудочков; ишемией, возникающей в результате повышения частоты сердечных сокращений в покое; усилением предсердной эктопической активности [22]. Важно помнить, что гипертиреоз ассоциирован с нарушениями параметров свертывания крови, такими как укороченное активированное частичное тромбопластиновое время (АЧТВ), повышенный уровень фибриногена и повышенная активность фактора VII и фактора X у пациентов с синусовым ритмом [27]; все это увеличивает опасность образования сердечных тромбов. Гипертиреоз вызывает возрастание риска серьезных сердечно-сосудистых событий на 16%, а также вносит вклад в повышение смертности от ССЗ [29].

Современную актуальность проблемы ФП и ее прогноза подчеркивают результаты анализа базы данных Корейской национальной службы медицинского страхования (n=9 751 705). Kim Y.G. et al. (2021) на основании 10-летнего наблюдения выявили связь впервые возникшей ФП с 4,6-кратным увеличением (p <0,001) риска летальных желудочковых аритмий: желудочковой тахикардии, трепетания желудочков и фибрилляции желудочков [30]. Правда, в данном исследовании при исключении многих коморбидных патологий не было указаний на анамнез заболеваний ЩЖ, тиреоидный статус у исследуемых пациентов не оценивался.

Аритмии у пациентов с гипертиреозом в основном являются предсердными, тогда как желудочковые аритмии у них встречаются редко, с частотой, аналогичной здоровым людям [31]. Желудочковая тахикардия обычно возникает в связи с основными структурными заболеваниями сердца или СН различной этиологии [11].

ВАРИАНТЫ СУБКЛИНИЧЕСКОГО ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗА И ЕГО ЭВОЛЮЦИЯ ВО ВЗАИМОСВЯЗИ С ПРОГНОЗОМ ФИБРИЛЛЯЦИИ ПРЕДСЕРДИЙ

По мнению экспертов, пациентов с СГ следует классифицировать на две категории по концентрации ТТГ в сыворотке крови: с низким, но определяемым уровнем (0,1–0,4 мМЕ/л) и подавленным (0,1 мМЕ/л) уровнем [32]. Исходя из такой общепризнанной градации, Osuna P.M. et al. (2017) добавляют к ней две степени: ТТГ 0,1–0,45 мМЕ/л – СГ 1-й степени; ТТГ <0,1 мМЕ/л – СГ 2-й степени [22]. В данной ситуации различие верхних значений указанного диапазона (0,4 или 0,45 мМЕ/л) может отражать нижний предел референсных значений, что зависит от используемой тест-системы.

Наиболее часто наблюдается экзогенный вариант СГ вследствие непреднамеренной чрезмерной заместительной терапии при гипотиреозе или супрессивной терапии ТТГ при злокачественных заболеваниях ЩЖ. Эндогенный СГ обычно ассоциирован с болезнью Грейвса или многоузловым токсическим зобом, а также автономно функционирующими одиночными узлами ЩЖ.

СГ выявляется достаточно часто, особенно у пожилых людей. Его распространенность варьирует в зависимости от возраста, пола, расы, генетической предрасположенности, йодного статуса и дефиниций СГ, которые могут различаться в разных исследованиях. Так, есть сообщения о распространенности СГ в разных странах в пределах от 1,3 до 10% с явным его преобладанием у женщин; при этом у пожилых людей этот показатель достигает 15,4% [33]. Эта форма заболевания ЩЖ привлекла внимание в последние годы именно из-за ее связи с ССЗ, в частности с ФП.

В крупном метаанализе, выполненном Yang G. et al. (2019), было выявлено влияние СГ на увеличение риска смерти от всех причин у пациентов с СН, но не на сердечную смерть и/или госпитализацию. При этом повышенный риск ФП служит одним из факторов риска общей смертности [14]. Авторы отмечают, что количество исследований, сообщающих о связи между гипертиреозом и сердечной смертью и/или госпитализацией, относительно невелико, что могло привести к недостатку статистической мощности. В более поздней публикации Vidili G. et al. (2021) на основе анализа базы данных PubMed и поисковой системы Google Scholar установлена явная связь СГ с началом ФП и, как следствие, с ишемическим инсультом. Данных о смертности по-прежнему немного, однако они предполагают возможное влияние СГ на сердечно-сосудистую систему [33].

В уже упоминавшейся публикации Tribulova N. et al. (2020) подчеркивается сильная ассоциация ФП и СГ с угрозой жизни, особенно из-за высокого риска эмболического инсульта даже при бессимптомной ФП у предрасположенных лиц (например, пожилых) [18]. Gluvic Z. et al. (2021) представили взаимосвязи различных вариантов гипертиреозов с нарушениями ритма сердца и последующими сердечно-сосудистыми исходами (рис. 2) [34].

Важной задачей практической медицины является предотвращение возникновения и/или повторения наиболее частых или опасных для жизни сердечных аритмий, к которым относится ФП, что повышает интерес к ее субклиническому скринингу. И, наоборот, длительный СГ может увеличивать риск ФП, что требует анализа вариантов его течения.

Эволюция СГ может быть различной: от стабильности в течение многих лет и даже возвращения к эутиреозу до прогрессирования к явному гипертиреозу. Такая эволюция зависит от этиологии СГ. Так, в случае аутоиммунного происхождения он может быть преходящим, нормализуясь у 25–50% пациентов [35]. Иными словами, СГ способен исчезнуть спонтанно без лечения. Альтернативно он может носить временный характер в период лечения антитиреоидными препаратами или после радиойодтерапии (пострадиационный тиреоидит). Многолетний СГ с прогрессивным повышением уровня тиреоидных гормонов иногда предшествует явному гипертиреозу: такая картина нередко наблюдается у пациентов при многоузловом зобе и автономно функционирующей аденоме ЩЖ [32].

Biondi B. и Cooper D.S. в своей работе (2008) уточнили, что эндогенный и экзогенный СГ имеют разные гормональные характеристики [32]. Так, концентрация св. T4 в сыворотке может находиться на верхнем уровне референсного диапазона или быть существенно повышенной у многих пациентов на супрессивной терапии левотироксином натрия. В последнем случае у пациентов уровни св. Т3 обычно находятся в середине референса, а соотношение Т4/Т3 больше, чем у пациентов с эндогенным СГ. Действительно, в эволюции автономии ЩЖ (эндогенный вариант СГ) уровни Т3 в сыворотке начинают возрастать еще до повышения Т4. Кроме того, экзогенный СГ при супрессивной терапии характеризуется постоянным подавлением ТТГ и может отличаться от эндогенного СГ скоростью и продолжительностью подъема уровней тиреоидных гормонов [32].

Позднее было установлено, что у пациентов с многоузловым зобом функциональное состояние ЩЖ зависит от йодной характеристики региона: СГ относительно стабилен на протяжении многих лет в областях с дефицитом йода, однако у лиц из регионов с адекватным потреблением этого микроэлемента отмечен 10% риск развития явного гипертиреоза (например, на фоне токсического многоузлового зоба) в течение 5-летнего периода наблюдения [36]. Риск прогрессирования СГ у пациентов в значительной степени непредсказуем и в основном связан с исходным уровнем ТТГ, что отражает его роль в качестве чувствительного индикатора функции ЩЖ. На основании проспективных наблюдений данный риск представляется более высоким у лиц с ТТГ <0,1 мМЕ/л в сравнении с тем, у кого содержание этого гормона составляет 0,1–0,4 мМЕ/л; инициировать его может любой вариант фармакологической дозы йода – рентгенконтрастное вещество или лекарственные препараты (например, амиодарон) [33].

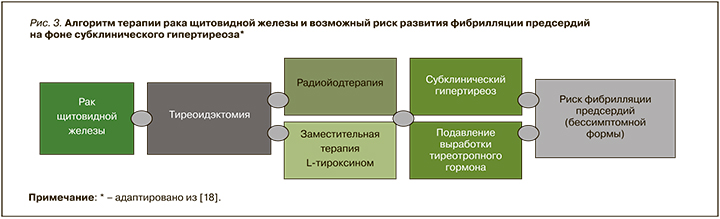

Учитывая возрастание числа случаев дисфункции и заболеваний ЩЖ, включая карциному, необходимо уделять особое внимание пациентам на супрессивной терапии, у которых симптоматическая ФП встречается редко. В подобной ситуации большая вероятность сочетания СГ с бессимптомной ФП требует повышенной настороженности клиницистов. Длительный СГ вследствие терапии, подавляющей ТТГ с помощью левотироксина натрия, может увеличивать риск ФП у пациентов после тиреоидэктомии (рис. 3). При этом гормоны ЩЖ из-за их многогранного клеточного действия следует рассматривать в качестве биомаркеров как при скрининге аритмий, так и при индивидуальном лечении [18]. Поскольку субклиническая тиреоидная дисфункция связана с неблагоприятным прогнозом при СН, а проверка функции ЩЖ является недорогой и простой, субклинический дистиреоз может быть полезным и многообещающим предиктором долгосрочного прогноза у пациентов с этим ССЗ [14].

ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗЫ И COVID-19

Особое внимание различные варианты гипертиреоза привлекают в период пандемии COVID-19, так как сообщается о высокой встречаемости явной и субклинической дисфункции ЩЖ в этой ситуации. Известно о случаях подострого тиреоидита (ПОТ) вследствие инфекции, вызванной SARS-CoV-2 [37]. ПОТ – воспалительное заболевание ЩЖ, как правило, вирусной этиологии, выступающее частой причиной тиреотоксикоза. Он характеризуется увеличенной болезненной ЩЖ с болью, отдающей в челюсть и ухо, биохимическими признаками тиреотоксикоза, повышением маркеров воспаления, таких как скорость оседания эритроцитов (СОЭ) и С-реактивный белок (СРБ), а также сниженным поглощением радиоактивного йода.

Lania A. et al. (2020) представили первые доказательства того, что COVID-19 может быть связан с высоким риском тиреотоксикоза вследствие активации системного иммунитета, вызванной SARS-CoV-2 [38]. В одноцентровом ретроспективном исследовании THYRCOV (n=287) при оценке тиреоидного статуса у больных COVID-19, госпитализированных не в палаты интенсивной терапии, у 58 (20,2%) из них был выявлен тиреотоксикоз (явный в 31 случае) в тесной связи с высоким уровнем циркулирующего интерлейкина 6 (ИЛ-6). У 16% пациентов с явным тиреотоксикозом развились тромбоэмболические явления, что оказалось более чем в два раза выше, чем у недавно зарегистрированных пациентов с COVID-19, госпитализированных в отделения неинтенсивной терапии [39]. Этот факт, наряду с высокой распространенностью ФП, тесной взаимосвязью между подавлением ТТГ и высокой смертностью, а также более длительной госпитализацией, позволяет предположить, что тиреотоксикоз может иметь существенное клиническое значение у пациентов с COVID-19.

Дифференциальный диагноз синдрома тиреотоксикоза в рамках THYRCOV не проводился, однако авторы отмечают, что по результатам комплексной оценки ряда пациентов с явным тиреотоксикозом, включавшей в том числе определение антител к рецепторам ТТГ (АТ к рТТГ), данных в пользу болезни Грейвса обнаружено не было. Имелись подозрения на тиреоидит, при этом характерного для ПОТ явного болевого синдрома не отмечалось. В связи с этим отдельного внимания заслуживает так называемый silent («тихий») тиреоидит, впервые описанный на фоне COVID-19 испанскими исследователями Barahona San Millan R. et al. (2020) [40]. При отсутствии жалоб со стороны наблюдаемого пациента они тем не менее выявили у него тахикардию на фоне повышения Т4 и подавления ТТГ при ярких биохимических признаках воспаления (резкое увеличение СОЭ, повышение СРБ, ИЛ-6 и отсутствие функциональной активности ЩЖ при сцинтиграфии). Ситуации «тихого» тиреоидита со склонностью к саморазрешению следует иметь в виду при проведении дифференциального диагноза эндогенного гипертиреоза и выборе индивидуальной тактики лечения.

К настоящему времени накопилось достаточно данных и о взаимосвязи COVID-19 с болезнью Грейвса. О первых двух случаях этого заболевания, возникших после заражения SARS-CoV-2, сообщили Mateu-Salat M. et al. (2020): один случай был первичным, другой – после 25-летней ремиссии [41]. Позднее было показано, что SARS-CoV-2 может вызывать болезнь Грейвса у пациентов после COVID-19, и ключевую роль здесь играют аутоиммунные механизмы. Факторы риска, коморбидные заболевания и варианты лечения болезни Грейвса, диагностированной на фоне COVID-19 (в острой его стадии или позднее), представлены в аналитическом обзоре Murugan A.K. и Alzahrani A.S. (2021) [42]. Пациенты с ранее выявленным и плохо леченным гипертиреозом, по-видимому, подвергаются большему риску заражения SARS-CoV-2 и связанных с ним осложнений COVID-19. Более того, новая коронавирусная инфекция рассматривается как потенциальный триггер тиреотоксического криза (thyroid storm) [43].

Хотя основным этиологическим фактором подострого тиреоидита выступают вирусы, в то же время сообщается и о ПОТ, индуцированном мРНК-вакцинами против SARS-CoV-2 [44]. Подобная ситуация объясняется воспалительным аутоиммунным синдромом, индуцированном адъювантами (АСИА), который охватывает широкий спектр состояний, включая поствакцинальные явления [45]. Было высказано предположение, что АСИА – следствие нарушения регуляции как врожденной, так и адаптивной иммунной системы после воздействия адъюванта. Аутоиммунный воспалительный синдром, вызванный адъювантами, затрагивающими ЩЖ, может быть побочным эффектом вакцинации против SARS-CoV-2 и оставаться не диагностированным [46]. Случаи болезни Грейвса, индуцированные вакцинацией против SARS-CoV-2, зафиксированы после введения мРНК-вакцины [47].

Тесная связь аутоиммунных факторов в рамках пандемии COVID-19 с болезнью Грейвса, исходно аутоиммунным заболеванием, обусловливает повышенный интерес к ранее опубликованным данным о значительном проценте пациентов с этой болезнью, имеющих активирующие аутоантитела против β1-адренергических (AAβ1AR) и M2-мускариновых (AAM2R) рецепторов [48]. Повышенная частота выявления данных аутоантител наблюдалась в основном у пациентов с ФП. У больных с синусовым ритмом они присутствовали с частотой, на 10% превышающей таковую в общей популяции. Специфические для ЩЖ аутоантитела, такие как антитела к тиреопероксидазе и к рТТГ, при болезни Грейвса обнаруживаются у 75 и 90–95% пациентов соответственно. Генетические, экологические и эндогенные факторы, ответственные за патогенез болезни Грейвса, увеличивают склонность этих пациентов к выработке других аутоантител [49]. У больных с гипертиреозом Грейвса совместное присутствие AAβ1AR и AAM2R способствует автономно-индуцированному быстрому триггерному возбуждению в легочных венах и является самым сильным независимым предиктором ФП. Эти уникальные активирующие аутоантитела могут играть роль в возникновении и поддержании ФП у данной популяции пациентов [48].

ДИАГНОСТИЧЕСКАЯ ТАКТИКА С УЧЕТОМ ЧАСТОГО СОЧЕТАНИЯ ФИБРИЛЛЯЦИИ ПРЕДСЕРДИЙ И ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗОВ

При ведении пациентов с ФП клинические руководства рекомендуют измерение ТТГ в рамках диагностического обследования. Эта простая рекомендация по скринингу позволяет клиницистам верифицировать не выявленный гипертиреоз, способный повлиять на тактику лечения ФП. С другой стороны, руководства также предлагают проводить активный скрининг ФП у пациентов с известным гипертиреозом [50]. Иными словами, раннее выявление и эффективное лечение дисфункции ЩЖ у пациентов с аритмией является обязательным; в этом случае долгосрочный прогноз аритмии может быть улучшен [11] за счет снижения риска метаболических и сердечно-сосудистых побочных эффектов [21].

Приведенные рекомендации коррелируют с результатами крупного общенационального когортного исследования в Дании. При наблюдении в течение 13 лет пациентов с впервые возникшей ФП (n=143 623) была установлена значительно более высокая частота диагностированного гипертиреоза, особенно среди мужчин в возрасте от 51 до 60 лет, по сравнению с общей популяцией того же возраста без диагноза ФП. Эти результаты были подтверждены в дополнительном анализе пациентов (n=527 352), которым был выполнен скрининг тиреоидного статуса [51].

Показано, что от 55 до 75% пациентов с ФП и гипертиреозом при отсутствии других кардиологических заболеваний возвращаются к нормальному синусовому ритму в течение 3–6 мес после лечения тиреотоксического состояния [52]. Biondi B. (2018), уточняя ситуацию, подчеркивает, что спонтанный возврат к синусовому ритму часто происходит у благополучно пролеченных пациентов с гипертиреозом в возрасте до 50 лет с недавно диагностированной ФП, без основного заболевания сердца и с более низким систолическим артериальным давлением. Напротив, ФП, сохраняющаяся в течение 4 мес и более после контроля гипертиреоза, редко возвращается к синусовому ритму, особенно у пожилых людей и пациентов с ССЗ [28].

Соответственно у пациентов с явным гипертиреозом без ФП лечение ЩЖ одновременно служит важным фактором снижения риска этого потенциального осложнения. Также важно помнить, что гипертиреоз влияет на сердечно-сосудистую гемодинамику и приводит к СН с высоким выбросом, а на поздних стадиях – к дилатационной кардиомиопатии; следовательно, раннее и эффективное лечение гипертиреоза может предупредить застойную СН [22]. Таким образом, раннее и эффективное лечение гипертиреоза – ключ к предотвращению как тиреотоксической кардиомиопатии, так и ФП.

ПОДХОДЫ К ЛЕЧЕНИЮ: ЯВНЫЙ ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗ И ФИБРИЛЛЯЦИЯ ПРЕДСЕРДИЙ

Базовые принципы терапии гипертиреозов обобщены в обзоре литературы Reddy V. et al. (2017) [21]. Основой лечения большинства гипертиреозов (болезни Грейвса, токсического многоузлового зоба либо токсической аденомы) служат бета-блокаторы и антитиреоидные препараты группы тионамидов: пропилтиоурацил, а также карбимазол и метимазол с действующим веществом тиамазол (МНН). Карбимазол (в настоящее время не зарегистрирован в России) является пролекарством, которое декарбоксилируется в печени с образованием тиамазола. Все тионамиды всасываются немедленно и накапливаются в ЩЖ, тормозя процесс синтеза тиреоидных гормонов. Пропилтиоурацил в больших дозах ингибирует дейодирование Т4 в Т3 в периферических органах (печени или почках), что может вызывать серьезные побочные эффекты, такие как тяжелое заболевание печени и васкулит [20].

Терапия блокаторами β-адренорецепторов – первая линия лечения тахиаритмий на фоне тиреотоксикоза при отсутствии декомпенсированной застойной СН. Основанием для применения препаратов этого класса в лечении ФП при гипертиреозе является контроль частоты сердечных сокращений [53]. Влияние неселективного бета-блокатора пропранолола на снижение периферической конверсии Т4 в Т3 имеет незначительную терапевтическую ценность; кардиоселективные препараты с более длительным периодом полувыведения столь же эффективны [54]. В то же время бета-блокаторы мало влияют на преобразование ФП в синусовый ритм или на гипертиреоз, тогда как тионамиды могут восстановить синусовый ритм в течение нескольких месяцев у большинства пациентов с гипертиреозом. Таким образом, лечение сопутствующего гипертиреоза представляется важным направлением в контексте долгосрочной терапии ФП [20].

У пациентов с неустойчивым гемодинамическим статусом также можно рассмотреть использование дигоксина. Однако в этом случае следует соблюдать осторожность из-за фармакокинетических особенностей и риска развития токсических побочных эффектов этого препарата [55].

У пациентов, которым противопоказана терапия бета-блокаторами, другие варианты лечения включают применение недигидропиридиновых блокаторов кальциевых каналов – дилтиазема или верапамила. Однако назначения этих препаратов следует избегать у пациентов со сниженной фракцией выброса или гемодинамической нестабильностью из-за сильного отрицательного инотропного эффекта. Амиодарон может использоваться в острых случаях ФП с целью перевода пациента в нормальный синусовый ритм в сочетании с антитиреоидными препаратами для снижения вероятности ухудшения гипертиреоза. Однако в этом случае следует соблюдать осторожность из-за риска тромбогенных осложнений при отсутствии надлежащей антикоагулянтной терапии [21].

Существуют две основные рекомендации относительно антикоагулянтной терапии у пациентов с ФП и гипертиреозом. По данным Американского колледжа торакальных врачей, гипертиреоз не является независимым фактором риска тромбоза у пациентов с ФП, и назначение антикоагулянтной терапии должно основываться на традиционной шкале CHA2-DS2-VASc [56]. Вместе с тем, по данным Американского колледжа кардиологов, гипертиреоз независимо увеличивает риск развития инсульта или тромбоза, а значит, пациенты должны получать антикоагулянты во время фазы гипертиреоза независимо от результатов оценки по шкале CHA2DS2-VASC [57]. В широко цитируемом исследовании de Souza M.V. et al. (2012) было обнаружено, что только возраст служит точным предиктором тромбогенной среды, тогда как остальные факторы риска имеют низкую результативность [58]. Ссылаясь на это исследование, Reddy V. et al. (2017) считают, что решение о начале антикоагулянтной терапии у пациентов с гипертиреозом и ФП в идеале должно приниматься на индивидуальной основе [21].

АМИОДАРОН-ИНДУЦИРОВАННЫЙ ТИРЕОТОКСИКОЗ

Амиодарон-индуцированный тиреотоксикоз (АМИТ) является клинически значимым пересечением дисфункции ЩЖ и ФП. Амиодарон – одно из рекомендуемых антиаритмических средств для кардиоверсии ФП и поддержания синусового ритма, особенно при структурных заболеваниях сердца и систолической дисфункции левого желудочка [50]. Однако длительное его применение сопряжено с риском развития ряда серьезных нежелательных явлений, включая дистиреозы. Каждая молекула амиодарона содержит два атома йода, поэтому после метаболизма 100 мг препарата печенью высвобождается примерно 3 мг йода [59]. Кроме того, вследствие своей липофильности амиодарон концентрируется в тканях, богатых жировой тканью, длительно выводится из организма (оценочный период полувыведения 2–3 мес) и иногда проявляет токсическое действие даже через несколько недель или месяцев после прекращения приема, что может приводить к АМИТ. Эта проблема, несомненно, заслуживает внимания на фоне пандемии с учетом увеличения частоты дистиреозов и ФП вследствие COVID-19.

Клинические эффекты амиодарона зависят от функции ЩЖ и йодного статуса каждого человека [60]. Поэтому перед началом приема препарата очень важно оценить тиреоидный статус пациента [59]. Большинство больных на фоне лечения амиодароном остается в эутиреоидном состоянии (>70%), в то время как примерно у 5–22% наблюдается гипотиреоз и у 2–9,6% – гипертиреоз [61].

Лечение АМИТ будет зависеть от функции ЩЖ, наличия клинических признаков и состоять в отмене амиодарона, назначении антитиреоидной терапии и/или кортикостероидов. При наличии АМИТ необходимо проведение сложной дифференциальной диагностики между разными его вариантами. Так, АМИТ I типа вызывает повышенный синтез Т4 и Т3 из-за избытка йода в амиодароне, тогда как АИТ II типа представляет собой деструктивный процесс, сопровождающийся избыточным высвобождением Т4 и Т3 без фактического их синтеза. Эти две патологии требуют специальных стратегий лечения и специализированной эндокринной помощи [50].

ДИСКУССИЯ О ТЕРАПИИ СУБКЛИНИЧЕСКОГО ГИПЕРТИРЕОЗА В КОНТЕКСТЕ ФИБРИЛЛЯЦИИ ПРЕДСЕРДИЙ

Последние 5 лет в мировом медицинском сообществе доминирует следующая точка зрения: ассоциации субклинических гипертиреозов с нарушениями ритма, СН и инсультом не вызывают сомнений, однако по-прежнему отсутствуют данные о положительных эффектах от лечения СГ [22, 33]. Решение о терапии СГ обычно принимается исходя из клинической оценки состояния больного и опыта врача после тщательного исследования пациента на предмет сопутствующих заболеваний. Tribulova N. et al. (2020) рекомендуют после подтверждения наличия СГ вторым тестом предложить лечение пожилым пациентам, особенно имеющим повышенный риск ФП [18]. Данных для однозначных выводов о необходимости рутинного лечения СГ у молодых и бессимптомных пациентов пока недостаточно: проспективные исследования, посвященные терапии этого состояния, довольно скудны, в них не было контрольной группы [18]. Также отсутствует информация о том, следует ли начинать лечение в случае впервые диагностированного СГ у пациента с предшествующей ФП [50].

В клинических рекомендациях 2015 г. Европейской тиреоидной ассоциацией (European Thyroid Association, ETA) предлагается лечить СГ 2-й степени у пациентов старше 65 лет и рассматривать возможность лечения более легкой степени СГ при наличии ССЗ либо других значимых сопутствующих заболеваний или факторов риска [62]. Гайдлайны Американской тиреоидной ассоциации (American Thyroid Association, ATA) 2016 г. также убедительно аргументируют целесообразность лечения СГ у пожилых пациентов с целью предотвращения аритмий и возможного последующего инсульта. Менее ясно, следует ли лечить более молодых пациентов по тем же профилактическим показаниям. Актуальные на тот момент данные свидетельствовали о том, что относительные риски сердечно-сосудистой смертности и ФП повышены как у молодых, так и у пожилых пациентов с СГ. Однако абсолютный риск этих явлений у молодых пациентов очень низок, поэтому соотношение риска и пользы лечения более молодых пациентов с СГ остается неясным. В этих случаях названные гайдлайны рекомендовали использовать клиническую оценку состояния больного, а решение о терапии принимать индивидуально [63]. Уточняя эту позицию, Gencer B. et al. (2022) считают, что лечение СГ следует рассматривать у пациентов старше 65 лет с уровнем ТТГ <0,4 мМЕ/л или у более молодых пациентов с ТТГ <0,1 мМЕ/л; кроме того, оправдано выполнять скрининг на ФП у пациентов с известным гипертиреозом [50].

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Гипертиреоз, как явный, так и субклинический, вследствие прямого влияния на электрофизиологию сердца способствует развитию сердечных аритмий, в основном ФП. Большая частота новых случаев ФП на фоне COVID-19 с высоким числом осложнений и повышенной 60-дневной смертностью, вероятно, обусловлена наличием у пациентов системных заболеваний, а не только прямым воздействием SARS-CoV-2. Одновременно в этой ситуации привлекает внимание высокая встречаемость явного и субклинического гипертиреоза различных вариантов – эндогенного (вследствие аутоиммунной болезни Грейвса и деструктивных тиреоидитов) и экзогенного (вследствие супрессивной или чрезмерной заместительной терапии левотироксином натрия). Тесная взаимосвязь между подавлением ТТГ и высокой смертностью, более частые тромбоэмболические осложнения при ФП в сочетании с гипертиреозом, а также более длительная госпитализация позволяют предположить, что тиреотоксикоз может иметь немалое клиническое значение у пациентов с COVID-19. Продолжающаяся дискуссия по поводу диагностической и лечебной тактики при часто встречающемся сочетании ФП и гипертиреоза диктует необходимость детальной индивидуальной оценки клинической ситуации и междисциплинарного решения.