ВВЕДЕНИЕ

Внебольничная пневмония (ВП) является одним из наиболее распространенных заболеваний и представляет собой острую инфекцию легочной паренхимы, диагностированную в случае развития заболевания вне стационара или в первые 48 ч с момента госпитализации. Заболеваемость ВП в России в 2019 г. составила 410 на 100 тыс. населения, а ежегодная заболеваемость в Европе варьирует в пределах 20,6–79,9 случаев на 10 000 человеко-лет [1–3].

По данным Всемирной организации здравоохранения, инфекции нижних дыхательных путей выступают основной инфекционной причиной смерти во всем мире: на них приходится 6,1% всех смертей [4]. В структуре смертности от болезней органов дыхания в России в 2019 г. доля пневмоний составляет 41,9% [5]. У пациентов пожилого и старческого возраста при наличии серьезной сопутствующей патологии (хронической обструктивной болезни легких, злокачественных новообразований, алкоголизма, сахарного диабета, сердечной недостаточности и др.), а также в случае тяжелого течения ВП уровень летальности достигает 15–58%, в то время как у лиц молодого и среднего возраста без сопутствующих заболеваний и нетяжелом течении ВП этот показатель находится в пределах 1–3% [6].

Ряд особенностей осложняет ведение пациентов с ВП:

- преимущественно эмпирический подбор антибактериальной терапии, обусловленный отсутствием данных о возбудителе;

- различие чувствительности к противомикробным препаратам наиболее распространенных возбудителей в разных регионах;

- недостаточное освещение в большинстве клинических рекомендаций принципов ведения пожилых пациентов, для которых характерны мультиморбидность и полипрагмазия [7–9].

Учитывая эти особенности, в 2022 г. в официальном журнале Европейской федерации внутренней медицины (EFIM) – European Journal of internal Medicine – был опубликован критический обзор рекомендаций по ВП, целью которого явилась помощь практикующим врачам в принятии решений при ведении «сложных» иммунокомпетентных пациентов с острой ВП. Документ был подготовлен членами рабочей группы по ВП (РГ-ВП), в состав которой вошли члены EFIM [10]. Этот обзор стал вторым документом, подготовленным экспертами EFIM, после адаптации рекомендаций по легочной эмболии, представленной в начале 2022 г. [11].

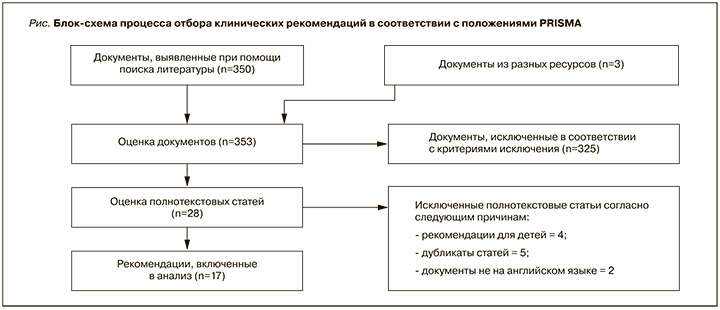

Экспертами был сформирован список из 5 вопросов в формате PICO (ПВСИ; П – пациент/P – patient, В – вмешательство/I – intervention; С – сравнение/C – comparison; И – исходы/O – outcomes), для решения которых в соответствии с положениями PRISMА были отобраны 17 недавно опубликованных протоколов клинических рекомендаций по ВП (рис.). Клинические рекомендации оценивались в соответствии с методологией оценки и адаптации таких рекомендаций EFIM [12] четырьмя членами РГ с использованием инструмента AGREE-II [13]. В окончательный анализ были включены 6 клинических рекомендаций [14–19].

В документе подробно излагаются ответы на наиболее актуальные вопросы, сформированные в виде PICO, относительно особенностей ведения пациентов в разных клинических ситуациях.

PICO 1. Следует ли идентифицировать вирус гриппа и другие респираторные вирусы у взрослых пациентов с ВП при первичной диагностике во время сезонных вспышек заболеваемости?

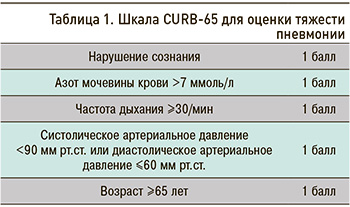

Экспертами РГ-ВП рекомендовано выполнение полимеразной цепной реакции (ПЦР) или серологических исследований в периоды повышенной активности респираторных вирусов у лиц с подозрением на пневмонию на основании клинических симптомов и/или рентгенологических данных, при средней тяжести заболевания (0–2 балла по шкале CURB-65; табл. 1) [17]. При тяжелом течении пневмонии (3–5 баллов по шкале CURB-65) рекомендован анализ мокроты или других биоматериалов из дыхательных путей методом ПЦР (наилучший вариант) или прямой иммунофлюоресценции (либо другого теста на обнаружение антигена) для уточнения вирусной этиологии. Сила рекомендации (СР) – сильная, уровень качества доказательности (УКД) – низкий [14, 18].

Метод ПЦР при его доступности предпочтителен для определения респираторных вирусов и атипичных возбудителей [15]. Парные серологические тесты могут использоваться только в эпидемиологических целях в случае высокой вероятности наличия вирусного возбудителя, когда последний не был выявлен микробиологическими методами (например, посев, определение антигена в моче, ПЦР), или в отсутствие положительной динамики у пациентов при тяжелом течении пневмонии на фоне применения бета-лактамных антибиотиков.

PICO 2. Следует ли применять прогностические шкалы для решения вопроса о госпитализации пациентов с ВП в терапевтическое отделение или отделение интенсивной терапии?

Эксперты РГ-ВП рекомендуют использование прогностических шкал, оценивающих тяжесть заболевания, в качестве дополнительного метода для принятия решения о необходимости госпитализации. При этом следует учитывать тяжесть состояния пациента с обязательной оценкой коморбидной патологии и социально-экономического статуса: легкая степень тяжести (лечение дома), средняя степень (госпитализация в терапевтическое отделение) или тяжелая степень (госпитализация в отделение интенсивной терапии). СР – сильная, УКД – средний [14–18].

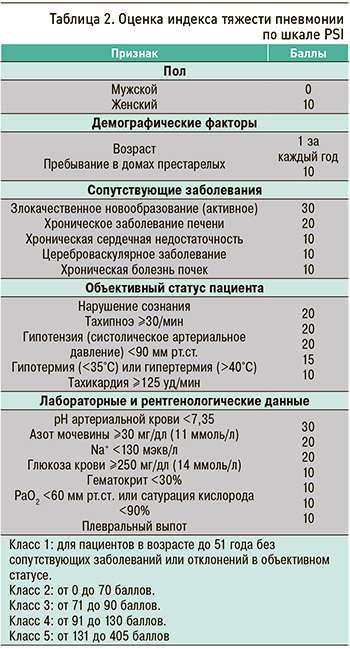

Для обеспечения единого подхода к оценке тяжести клинического состояния пациентов эксперты РГ-ВП рекомендуют врачам терапевтам использовать только одну из утвержденных шкал: CURB-65 (см. табл. 1) или PSI (Индекс тяжести пневмонии; табл. 2). Обе шкалы имеют высокую прогностическую значимость при оценке 30-дневной летальности у пациентов, госпитализированных с ВП [20, 21]. СР – сильная, УКД – средний [15]. При этом РГ не отдает предпочтения какой-либо из этих шкал в сравнении с другой [10].

В условиях амбулаторного звена следует использовать упрощенную шкалу CRB-65: СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [14, 18].

В документе определены показания для госпитализации пациентов с ВП:

- наличие симптомов или признаков, указывающих на более серьезное заболевание или состояние (например сердечно-сосудистая и дыхательная недостаточность или сепсис);

- сохранение лихорадки на фоне приема антибиотиков в течение последних 48 ч или наличие более одного признака, указывающего на нестабильность состояния (систолическое артериальное давление менее 90 мм рт.ст., частота сердечных сокращений более 100 ударов в минуту, частота дыханий более 24 в минуту, сатурация кислорода менее 90% при дыхании атмосферным воздухом или парциальное давление кислорода в артериальной крови менее 60 мм рт.ст.);

- невозможность приема пациентом лекарственных средств перорально (целесообразно оценить возможность введения антибактериальных препаратов внутривенно в условиях места жительства пациента или в поликлинике). СР – сильная, УКД – высокий [14, 16, 18];

- пожилой возраст пациента и наличие коморбидной патологии с высоким риском осложнений: сахарного диабета (СД), сердечной недостаточности, хронической обструктивной болезни легких (ХОБЛ) средней и тяжелой степени тяжести, заболеваний печени, почек или злокачественных новообразований (ЗНО). УКД – низкий [19].

При суммарном количестве баллов от 4 до 5 по шкале CURB-65 необходимо рассмотреть вопрос о переводе пациента в отделение интенсивной терапии: СР – сильная, УКД – высокий [18].

В отсутствие ожидаемого улучшения следует рассмотреть возможность проведения дополнительного обследования (например, бронхоальвеолярного лаважа) или перевода пациента в отделение интенсивной терапии: СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [18].

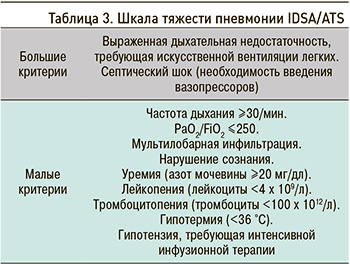

Экстренная госпитализация в отделение интенсивной терапии рекомендуется пациентам с гипотензией, требующей вазопрессорной поддержки, или дыхательной недостаточностью, требующей проведения искусственной вентиляции легких (ИВЛ): СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [14, 17, 18]. Для остальных пациентов эксперты РГ-ВП предлагают использовать малые критерии шкалы IDSA/ATS (табл. 3) для определения стратегии более интенсивного лечения. Наличие трех и более малых критериев может потребовать госпитализации в отделение интенсивной терапии: УКД – низкий [17].

Эксперты уточняют, что критерии для госпитализации в отделение интенсивной терапии следует применить прежде всего в качестве индикаторов необходимости интенсификации лечения.

PICO 3. Следует ли оценивать межлекарственные взаимодействия у взрослых мультиморбидных пациентов с ВП при выборе антимикробной терапии?

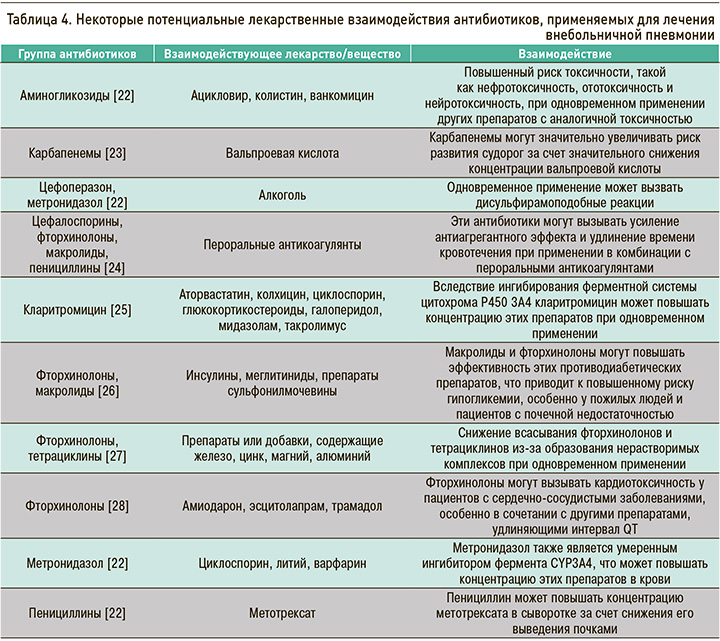

Согласно рекомендациям экспертов РГ-ВП, перед началом антибактериальной терапии необходимо оценивать потенциальные межлекарственные взаимодействия с учетом мультиморбидного фона, особенно у пожилых пациентов с ВП: СР – сильная, УКД – высокий [16]. Потенциальные лекарственные взаимодействия антибиотиков для лечения ВП с препаратами других лекарственных групп, используемых в терапии сопутствующей патологии, представлены в таблице 4.

С целью уменьшения временны'х затрат на оценку лекарственных взаимодействий рекомендовано обращение к электронным базам данных с возможностью проверки межлекарственных взаимодействий активных веществ лекарственных средств (в частности, в России – справочник Видаль «Лекарственные препараты в России»: https://www.vidal.ru/drugs/interaction/new; система искусственного интеллекта «Киберис»: https://kiberis.ru/).

При назначении медикаментозной терапии пожилым пациентам с ВП также необходимо учитывать возможные нарушения функции печени и почек, способные приводить к увеличению объема распределения, удлинению периода полувыведения и снижению клиренса, а также риску развития побочных эффектов лекарств [29].

PICO 4. Какие факторы необходимо учитывать перед началом антимикробной терапии у взрослых пациентов с ВП?

В амбулаторных условиях для пациентов без сопутствующих заболеваний в качестве препаратов первой линии рекомендованы амоксициллин или макролиды (кларитромицин, азитромицин) либо доксициклин: СР – сильная, УКД – средний [17, 30]. Использование макролидов или доксициклина целесообразно только при низкой резистентности. В регионах с высокой резистентностью монотерапия этими препаратами не рекомендуется [15, 19]. Для пациентов с сопутствующими заболеваниями (хроническими заболеваниями сердца, легких, печени или почек, СД, алкоголизмом, ЗНО или аспленией) рекомендована комбинированная терапия (бета-лактам и макролид) или монотерапия респираторными фторхинолонами. В странах с низким уровнем резистентности необходимо следовать национальным рекомендациям (лечение амоксициллином, доксициклином или макролидом). СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [17].

Выбор антибиотика необходимо осуществлять с учетом региональной резистентности к противомикробным препаратам, соотношения пользы и риска, аллергологического анамнеза, наличия перекрестных реакций и побочных эффектов препарата, стоимости лечения [16, 17, 19]. Следует отдавать предпочтение пероральному приему антибактериальных препаратов, при его невозможности необходимо рассмотреть альтернативу в виде парентерального введения лекарственных средств в домашних условиях или в поликлинике по месту жительства [16].

У госпитализированных пациентов перед началом терапии препаратами широкого спектра действия необходимо оценить и выявить факторы риска инфицирования метициллин-резистентным золотистым стафилококком (MRSA) и Pseudomonas (предшествующая изоляция, недавняя госпитализация или предшествующее лечение парентеральными антибиотиками, употребление алкоголя, заболевание легких и длительное применение глюкокортикостероидов): СР – сильная, УКД – средний [14, 17]. Если пациенту не показано лечение в условиях отделения интенсивной терапии, рекомендуется комбинированная терапия бета-лактамами и макролидами или монотерапия респираторными фторхинолонами. При наличии аллергической реакции или противопоказаний к применению макролидов и фторхинолонов в качестве альтернативы возможно использование доксициклина. СР – сильная, УКД – средний [17].

В отделении интенсивной терапии пациентам без факторов риска MRSA и Pseudomonas рекомендована комбинированная терапия бета-лактамами и макролидами или бета-лактамами и респираторными фторхинолонами: СР – сильная, УКД – средний [14, 17].

Эксперты РГ-ВП рассматривают возможность проведения анализа мочи для выявления пневмококка всем пациентам с тяжелым течением ВП (УКД – низкий) [14, 15, 17], а при наличии специфических факторов риска и во время вспышек заболеваемости – для определения антигенов легионеллы. СР – сильная, УКД – средний [18].

При подозрении на абсцесс легкого или эмпиему следует рассмотреть назначение бета-лактамов/ингибиторов бета-лактамаз или комбинации цефалоспорина и клиндамицина с учетом вероятности резистентности (например, недавнего применения антибиотиков или госпитализации), уровня резистентности к этим противомикробным препаратам в регионе, где проживает пациент, и риска инфекции C. difficile. УКД – очень низкий [17].

При отсроченном ответе на антимикробную терапию или наличии сопутствующих заболеваний, таких как СД, хроническая болезнь почек, ХОБЛ, или же при длительном применении глюкокортикостероидов необходимо исключить наличие туберкулеза. При подозрении на туберкулез следует избегать применения респираторных фторхинолонов. СР – слабая, УКД – низкий [14].

Фторхинолоны следует с осторожностью применять при лечении пожилых пациентов из-за побочных эффектов со стороны опорно-двигательного аппарата (повреждения/разрыва сухожилий) и нервной системы, а также избегать одновременного назначения с кортикостероидами [16].

PICO 5. Необходима ли оценка уровня биомаркеров инфекции у взрослых пациентов с ВП для контроля за назначением антибактериальной терапии?

Эксперты не рекомендуют определение лабораторных маркеров бактериальной инфекции на амбулаторном этапе: СР – сильная. УКД – высокий [19]. Вместе с тем рассматривается возможность оценки уровня С-реактивного белка (СРБ) для определения необходимости назначения антибиотиков при неясной клинической картине в условиях амбулаторного звена:

- при уровне СРБ ниже 20 мг/л в течение более 24 ч у симптомных пациентов наличие пневмонии маловероятно, антибактериальная терапия не рекомендована;

- при уровне СРБ от 20 до 100 мг/л назначение антибиотиков возможно при прогрессировании симптомов пневмонии;

- при уровне СРБ более 100 мг/л вероятно наличие пневмонии и показано назначение антибиотиков. СР – сильная. УКД – высокий [19, 31].

У пациентов с подозрением на COVID-19 низкий уровень СРБ свидетельствует о низкой вероятности вторичной бактериальной инфекции, тогда как высокий его уровень не позволяет сделать выводы о бактериальной или вирусной (SARS-COV-2) этиологии пневмонии: СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [32].

Прокальцитонин (ПКТ) более информативен, чем СРБ, для определения бактериальной ко- или суперинфекции у пациентов с COVID-19 [33]. Низкий уровень ПКТ в сочетании с характерной клинической картиной, по-видимому, служит более чувствительным маркером для выявления пациентов с COVID-19, которым не требуется антибактериальная терапия. Алгоритмы лечения с учетом уровня ПКТ могут позволить безопасно сократить применение антибиотиков у пациентов с пневмонией COVID-19 [34–38].

СРБ следует измерять в 1-й и 3–4-й дни, особенно при нестабильном клиническом состоянии. Отсутствие снижения СРБ на 50% к 4-му дню ассоциировано с пятикратным увеличением риска смертности, развития осложнений и потребности в ИВЛ. У пациентов без положительной клинической динамики для оценки риска неэффективности лечения и развития осложнений возможно серийное определение уровня СРБ. В такой ситуации также может быть целесообразна оценка уровня ПКТ. СР – сильная, УКД – низкий [14, 18, 39].

Комментируя эту рекомендацию, эксперты обращают внимание на то, что отсутствие снижения уровня биомаркеров на 50% у пациента с хорошим клиническим ответом на терапию не следует рассматривать как критерий для продления сроков антибиотикотерапии.

При решении вопроса о длительности антибактериальной терапии важно учитывать стабильность клинического состояния пациента, при наличии которой антибиотикотерапия должна быть прекращена в общей сложности через 5 дней: СР – сильная, УКД – средний [17].

Эмпирическая антибактериальная терапия рекомендована взрослым пациентам с клиническими признаками и рентгенологически подтвержденной ВП, независимо от исходного сывороточного уровня ПКТ: СР – сильная, УКД – средний [17].

ПКТ может быть полезен для подтверждения бактериальной инфекции, а его значение служит ориентиром для определения продолжительности лечения, особенно у пациентов с явным клиническим улучшением: СР – сильная, УКД – высокий [14].

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ

Таким образом, при первичной диагностике ВП во время сезонных вспышек заболеваемости вирусной инфекции метод ПЦР в случае его доступности предпочтителен для определения респираторных вирусов и атипичных возбудителей. Прогностические шкалы (CURB-65 или PSI) рассматриваются в качестве дополнительного метода для решения вопроса о необходимости и месте госпитализации; в амбулаторных условиях следует использовать упрощенную шкалу CRB-65. Экстренная госпитализация в отделение интенсивной терапии рекомендуется пациентам с гипотензией или дыхательной недостаточностью, требующих вазопрессорной поддержки или ИВЛ соответственно. Перед началом антибактериальной терапии необходимо оценить потенциальные межлекарственные взаимодействия, особенно у пожилых мультиморбидных пациентов с ВП [40].

На догоспитальном этапе для пациентов без сопутствующих заболеваний в качестве препаратов первой линии рекомендованы амоксициллин или макролиды либо доксициклин, с сопутствующими заболеваниями – комбинированная терапия (бета-лактам и макролид) или монотерапия респираторными фторхинолонами. Предпочтителен пероральный прием антибактериальных препаратов, при его невозможности осуществляется парентеральное введение лекарственных средств в домашних условиях или в поликлинике. У госпитализированных пациентов перед началом терапии необходимо оценить факторы риска инфицирования метициллин-резистентным золотистым стафилококком и Pseudomonas и рекомендовать комбинированную терапию бета-лактамами и макролидами или монотерапию респираторными фторхинолонами, в отделении интенсивной терапии – комбинированную терапию бета-лактамами и макролидами или бета-лактамами и респираторными фторхинолонами.

Определение лабораторных маркеров бактериальной инфекции на амбулаторном этапе не рекомендовано, однако рассматривается возможность оценки уровня СРБ для решения вопроса о необходимости назначения антибиотиков при неясной клинической картине. Эмпирическая антибактериальная терапия рекомендована при клинических признаках и рентгенологически подтвержденной ВП. ПКТ может быть полезен для подтверждения бактериальной инфекции, а его значение – для определения длительности лечения, особенно на фоне клинического улучшения.

Процесс подготовки обсуждаемого документа стартовал до пандемии новой коронавирусной инфекции, что обусловливает малое количество данных о COVID-19. В представленных рекомендациях не рассматриваются подходы к ведению пациентов с иммунодефицитными состояниями, включая онкологические заболевания и/или ВИЧ, что также является ограничением данного документа.